This is an article I wrote for a magazine called Lotus Realm. The article was entitled “Catalysts for Change” but the above was my original choice of title. The four catalysts being the four Brahma Vihara meditations practices. If you want to have the articel in its original format , you download it as a PDF here. If not then read on ….

CATALYSTS make things happen. They make things happen under circumstances in which they would not normally happen. Catalysts speed things up.

Scientists know about chemical catalysts. They know that a good catalyst will help compounds react at lower temperatures and at lower pressures – in other words, under conditions which are easier to set up and maintain. Chemists also know that the catalyst itself is not changed in this process. It promotes change but is not itself changed. It retains its purity.

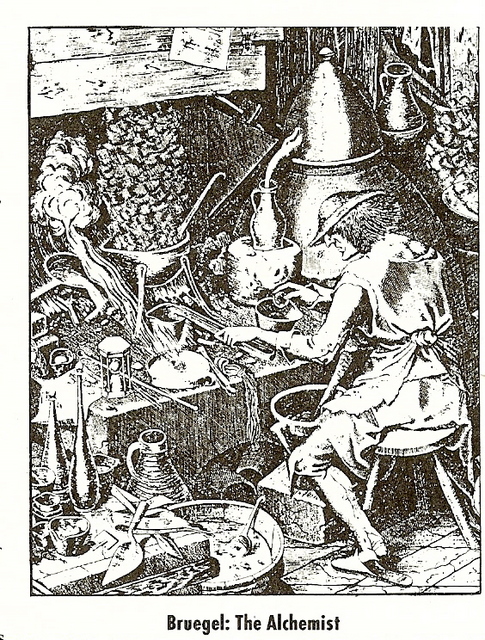

Alchemists also knew about catalysts. Alchemists and their theories and experiments were the forebears of modern chemistry, but unlike modern chemists, alchemists practised their art in the belief that the state of mind of the alchemist affected the outcome of the catalytic experiments.Both the substances and the experimenter needed to be as pure as possible if the best outcome was to be obtained. Their catalyst par excellence was the fabled Philosopher’s Stone which would turn base metal into gold. To work with the Stone, the alchemist needed to have a pure mind. Without such a mind, nothing could be produced that would not itself be tainted with imperfection. Since gold was the perfect substance, whatever the imperfect alchemist produced would not be gold but only a flawed imitation of the real thing.

From a 20th century perspective, the ideas of the alchemist may seem ridiculous. Certainly much of it is chemically impossible – at least outside of nuclear reactors or the solar atmosphere. Modern chemists probably don’t think there is any scientific need to purify their own minds beyond the level of not falsifying results. Nevertheless there is still something fascinating about the alchemists and the task they set themselves. In the

perfected alchemist the spell-binding figure of the magician combines with the purity and renunciation of the hermit to create a powerful symbol – a perfected being who has solved the mystery of how to create the perfected substance.

Meditation is also a catalyst – it too promotes change and can do so under circumstances and conditions in which change has not yet begun. Just as chemical catalysts allow chemists to transform physical material of one sort into another sort, so meditation can catalyze our mind and change it from what it is now into an altogether more refined,

clearer and more deeply responsive kind of consciousness. Chemical catalysts can help create altogether new types of material – never observed till the completion of that particular experiment. Imagine the chemist’s excitement and exhilaration in watching the process unfold … knowing that noone has ever before seen what you are seeing, or

done what you are doing! With meditation what is being created is new to us but not, of course,new to mankind since it lets us retrace a process of change already mapped out by earlier generations of practitioners.

So – can meditation be as exciting as chemistry? Are we as dedicated to changing ourselves as a medieval alchemist in pursuit of erfection? I think we should be even more excited and more dedicated. Of course perhaps you have never thought that chemistry could be exciting anyway. How strange! Keep reading!

Chemical catalysts operate within the physical and biological realms. Meditation achieves its ends within the realm of our mind – throwing light on old patterns and half-glimpsed ideas and views; rooting out what hinders, freeing us from the poisons of greed, hatred and delusion, eventually allowing a completely new purified consciousness to emerge. Chemistry is limited. Meditation is not. (Limited though they are, chemistry and science are not in any basic conflict with the Dharma. It’s just that the Dharma has the greater perspective. It’s the catalyst par excellence.)

THE FOUR GREAT CATALYSTS OF BEING

These reflections apply to meditation generally, but there is one set of meditation practices to which they are particularly pertinent. These are the practices for developing the four Brahma Viharas or Sublime Abodes of loving kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. The Brahma Viharas are also known as the four great catalysts of being! Let’s look at the Dharmic catalytic process that they offer us.

It’s not very difficult to wish to eradicate hatred or greed or ignorance from our mind. It is difficult to maintain that wish strongly over a long time. It’s not that difficult to recognise those states in their more extreme forms, particularly when we are seeing them in other people. It’s a lot harder to identify them in their more cunning, plausible, even mesmerising appearances, particularly within ourselves. Why is this? To answer this question we’ll need to move one step back to what we experience just before greed or hatred appear.

In a way it’s very straightforward. Just before one of those great impurities of mind appears, we experience a feeling (Pali: vedana) which is either pleasant or unpleasant or somewhere between the two. If it’s pleasant we want to keep on feeling it and if it’s unpleasant we want it to stop. Out of that simple process emerge all the emotions that humankind is prey to. Being prey to something is to be hunted and chased, perhaps being caught and killed. Being prey to these emotions we are at their mercy. But they are not merciful! These emotions lead us round and round an unending cycle of feeling and our reaction to it.

Continuity of purpose is one of the faculties which we are exhorted to develop if we want to practise the Dharma. Maybe it would be helpful for us to realize that we already experience continuity: we show great constancy in letting ourselves be a host for these mental impurities. What we need to do is show some constancy in getting rid of them!

Each time we react with craving or illwill we reinforce old poisonous patterns. We create ever stronger tendencies in our minds. We give them more life. This is how we create the volitional activity (Pali: sankharas, more commonly known in their Sanskrit form, samskaras) which become the emotional skeleton for our future, the framework around which the rest of ourselves will crystallize.

Rather than getting downhearted faced with this sort of home truth, maybe it’s more useful to let it become fuel for our future attempts to change. Let’s just acknowledge that maybe it’s going to be tougher than we expected and will need more determination on our part. To put it into chemical terms – we need a more effective catalyst to cope with our present conditions. This is where meditation comes into its own. Meditation gives us the opportunity to create a new set of samskaras for ourselves, a set that will allow us to spiral up into a more refined, steadfast and skilfully directed kind of consciousness, which is eventually able to experience things as they Really Are.

Let’s go back to pleasant and unpleasant feeling. The present fact is that we tend to respond to pleasure with craving: we want more. We need a better response than that. In the midst of painful feeling we tend to respond with aversion. We want to push it away. We need a better option than that, too. In neutral feeling what happens? Well, I usually get bored and want something more exciting – craving sets in! There are two aspects to changing all this. First of all we’ve got to want to change it; and secondly we need the means to do so.

Again, it’s not that difficult to understand that our present tendencies merely reinforce old spent a number of patterns. The crucial element in bringing change about is that our present volitions must years doing become painful to us. They even have to become consistently painful not just occasionally painful! research work in Feeling, vedana, must take on an aspect of unsatisfactoriness (Pali: dukkha) so that even chemistry. strongly pleasant feeling has just enough of a sharp tang to it that we stop and realize how careful we need to be in choosing our next move. And note the word ‘choose’. Unsatisfactoriness brings choice in its wake and with choice we are no longer so much the prey of those three great poisons. But to begin with we can just pay some attention to the impermanence

of even our most pleasant experiences; and maybe have some awareness of the pain brought about by repetitive unskilful behaviour.

Having managed to bring some measure of awareness of unsatisfactoriness into our mind, let’s congratulate ourselves! It means that we have begun the dharmic version of the purifying process to which those alchemists aspired. It means that the first Noble Truth has begun to trickle into our consciousness. And to take that on board, the Truth that in all experience there’ is an element of unsatisfactoriness, is no easy thing – perhaps today more than ever. In western society we are prey to a view that we deserve to be happy. The pursuit of happiness as an inalienable right is even enshrined in the Constitution of the United States! Unfortunately that happiness is not envisaged as being outside ordinary existence, Instead people are left pursuing happiness where it can never be found – a position just as ridiculous as the search for an actual Philosopher’s Stone. Influenced by this wrong view, we can feel we ought to be happy, and that to acknowledge painfulness must be wrong in itself or even unhealthy.However, the Dharma says that to acknowledge dukkha is the starting point of spiritual life. The first Noble Truth is not illustrative of a pessimistic Buddhist world view as some have claimed. It simply acknowledges the facts of human experience: the experience of unsatisfactoriness born of impermanence, and its accompanying wish for meaning in our lives. If we face up to it, this experience can galvanize us into action in pursuit of something beyond our current existence.

So – at length – we come to the means of achieving that greater meaning. We need better options with which to deal with pleasant and unpleasant feeling. They are waiting for us in the Brahma Viharas. To pleasant feeling we could respond with sympathetic joy and to unpleasant feeling we could respond with compassion. A simple formula to understand but difficult to embody. The Brahma Viharas also include loving kindness, which is the

foundation of compassion and sympathetic joy; and equanimity, which gives us a further means for deepening our understanding of the other three great catalysts. If compassion is the antidote to aversion and sympathetic joy the antidote to craving, then equanimity is the counterpart to the ignorance underlying those poisons; and loving kindness is the foundation to them all. It is, therefore, to loving kindness that we first have to turn.

LOVING KINDNESS – METTA

What I have had to acknowledge time and time again as I’ve tried to practise the Brahma Viharas is that if I cannot feel loving kindness (Pali: metta) for myself then I am unlikely to feel much loving kindness for anyone else either, much less can I develop the other Brahma Viharas.

One of the most crucial elements of metta is that it brings confidence. Just that – confidence. There are many ways in which we can lack confidence. After we’ve evaporated ‘off our more psychologically-based lack of confidence, we are left simply with the need to have confidence in ourselves as human beings who can practise the Dharma. When the Buddha was dealing with doubts in himself just before he gained Enlightenment, he called to mind all his previous practice and the fact that it gave him the right, as it were, to dare set himself the highest purpose of attaining the completely pure Enlightened state. That calling to mind of previous effort and commitment is symbolised in the earth-touching ‘mudra’ or hand gesture. Next time you are meditating and an inner voice asks who you are to be doing this, try the earth-touching mudra!

My reference to evaporating oil our more psychologically-based doubts is not meant to disown or underestimate those. However, we find that one of the great properties of metta is that it lets us step aside from our psychology. It gives us some objectivity about ourselves and helps put our efforts into developing faculties that go beyond our psychological problems and difficulties. Just as the Dharma shows up the limitations of chemistry, it also shows up the limitations of psychology.

All the Brahma Viharas have this catalyzing property. It’s the way that something new can come into being: our sense-based faculties can gradually change into spiritual faculties. The Buddha described the first such faculty as faith (Pali: saddhda) which is also translated as confidence- faith. The metta-bhavana meditation practice for the development of loving kindness is a means for developing this first spiritual faculty. By repeating the practice over and over again we gradually give ourselves the inner space to simply feel without our minds immediately leaping on to either craving or aversion. The more we do that, the greater the choice we have and the more we are living our life instead of it living us. That choice brings a sense of empowerment and responsibility and, if we are honest with ourselves, it will also increase our faith in the Dharma as we see it transforming us in the way it promised.

I’ve already mentioned that we need to transform our continuity from continuity of greed, hatred and delusion to continuity of another kind. Continuity of purpose is part of what is required. It is usually described in terms of time – we need to be able to recollect actions in our past and their consequences, and apply that knowledge to our present actions in order to be able to create the future which we want. In this sense continuity of purpose is connected with stopping ourselves falling prey to unskilful habits.

Continuity can also be thought about in another way: we need continuity of metta. We need to be able to respond with loving kindness over the whole spectrum of feeling. The Brahma Viharas are unconditional in that they admit of no exceptions – no person or situation is omitted. Over the whole spectrum, whether we meet the blissful, the addictive, the horrifying, the contented, the fearful, the entangling, the boring or the appalling – all these can become the occasion for the arising of metta if we apply the effort.

Perhaps we think that therefore this metta must be a great blazing fire of an emotion. Well, sometimes it is. But sometimes it is just a steady flame that refuses to go out despite the best efforts of our old inclinations. It is important to recognise the potential of that steadiness. It doesn’t matter if it’s a small flame if it is a constant, persistent flame. And it is constancy that can give us confidence in ourselves – our own experience of touching the ground of our practice.

COMPASSION – KARUNA.

Compassion arises when metta encounters suffering. We don’t need to do anything special to feel compassion beyond bringing together two conditions – the inner experience of metta and the recognition of somebody’s suffering. It

is not easy to bring these conditions together and keep them aligned with one another, but if we can do that we have created the conditions for karuna to arise. Establishing metta for ourselves and others is the first step in the karuna-bhavana practice. Metta is the foundation for all the Brahma Viharas. The second step is the bringing to mind of an actual suffering person and letting the metta we feel be touched by and respond to that person’s

suffering.

The suffering person could be ill or experiencing other unfortunate circumstances. They could be someone whose past actions are causing them suffering now. From there we extend the spectrum of situations in which we respond with compassion to include our friends, people we hardly know, people we dislike and finally to all sentient beings everywhere we can imagine them.

It is not difficult to think of places and events around the world which deserve a compassionate response from us. Global communications give us first hand accounts of wars and famines as they are happening. Natural and man-made disasters appear in our living-rooms only hours after they have brought sudden misery and sorrow into people’s lives. It’s not hard to feel sympathy for all that – yet we don’t always do so. The very speed and frequency with which these pictures appear sometimes makes us want to just turn the TV off. It’s all too much. Or maybe we have become immune to their impact and don’t feel anything much at all. It’s just another image flickering before our eyes.

This sort of non-response is an example of karuna slipping away into one or other of its ‘near enemies’. All the Brahma Viharas have their own particular near enemies – emotions which resemble the pure form but are actually contaminated by either craving or aversion. In the case of compassion, the tendency when we ask ourselves to face suffering is that we slip into aversion. When this happens, compassion turns into either horrified anxiety or the suffering overwhelms our metta and we are left feeling paralysed and impotent, wanting nothing more than to be rid of this very unpleasant experience. Sentimental pity is a well-known near enemy of compassion. It may get us to engage in doing all sorts of ‘good works’ but we are too much aware of ourselves, too aware of our own comparative good fortune. As we know, it is not a pleasant experience to be on the receiving end of this.

The best way to work with these enemies is to go back to individual real people again and, with the help of self-metta, try just to stay in touch with one person’s suffering at a time. As we practice this over and over again, gradually a new experience transpires – suffering becomes something we can meet face to face. Facing suffering and infusing the experience with metta creates another new experience – fearlessness. Fearlessness gives us confidence and lets us mobilize more energy and determination behind our practice. The catalytic transformation

continues.

SYMPATHETIC JOY – MUDITA

Just as compassion arises naturally when metta meets suffering, sympathetic joy arises when metta meets joy. It’s only necessary to bring the. two together and joy can be the occasion for more joy! It’s wonderful! It really works! Who would have thought it? As for the other Brahma Viharas, we begin with metta for ourselves. If we feel metta for ourselves, we won’t feel jealous of others’ good fortune. Instead we will simply feel joy! Admittedly, it is easier to say than to do and a few other basic materials are needed to let this catalyst really work well. One is confident that actions really do have consequences and that our own skilful actions will lead to pleasant consequences in the future.

The practice proceeds in much the same way as the karuna-bhavana, except that instead of bringing to mind a suffering person, we recollect a fortunate person, someone who is generally happy or who is enjoying happy circumstances in their life, and we rejoice in their happiness and talents.

Mudita’s near enemy arises when we begin to slip into craving the joy for ourselves. Vicarious satisfactbn arises. It’s a counterfeit emotion which masquerades as mudita and it can be quite difficult to recognise. Perhaps it’s best recognised by the characteristic of dependency it embodies. In the grip of this impurity we are no longer living our own life but have become dependent on someone else for our emotional experience. Like a parasite we steal their emotional lifeblood to give us sustenance. Again it’s by going back into the individual stages of the mudita-bhavana that we can best work with this kind of stealthy craving.

By practising mudita-bhavana, we’ll notice changes for the better. In a very down to earth sense, experiencing mudita is like having a clear conscience. For the moment at least, with no barriers or defences between us and other people, we can just appreciate and rejoice with them. It opens the door to delighting in people individually and in humanity as a whole with all its achievements and aspirations. It’s wonderful!

EQUANIMITY – UPEKKHA.

To recap: in transforming our reactions to pleasant and unpleasant feeling, we find compassion is the antidote to aversion; mudita the antidote to craving; and metta is the foundation for both. So what is equanimity?

In the upekkha-bhavana, it is neutral feeling which gives rise to equanimity. After a first stage of developing metta, the practice proceeds by bringing to mind a neutral person. The absence of any strong positive or negative feeling towards this person enables us to enter a more reflective state where we can, as it were, watch the passing of both good and bad fortune in this person’s life. We can reflect that they will no doubt experience both success and failure, love and grief, gain and loss as their life proceeds. When these sorts of reflections are imbued with metta a sort of kindly patience arises. Hardly knowing this neutral person, our reflections will be very general and this gives them an added power to catalyze our state of mind: everything we are thinking about this neutral person

applies also to ourselves and to everyone else we can imagine. Whatever change they are subject to, we will also undergo that change be it old age, families being born and growing up, unexpected illness, friendships growing and passing. This is very much a reflection about impermanence.

Sometimes these sorts of reflections arise spontaneously. As I was driving in the city one day, I found myself sitting at red lights. I watched two young men cross the road in front of me. They were in their twenties, looked fit and healthy, and were completely engrossed in their conversation. They walked on confidently together. A few hundred yards further on I stopped at another set of lights and suddenly realized the two men were in front of me again still talking, still friends, but now old, slow, bent, and hesitant of foot. Of course it wasn’t the same men. But to me the two scenes coalesced into one experience: impermanence.

Upekkha develops out of reflections like these. It requires the ability to hold compassion and mudita together at the same time. Not an easy task. Gradually it opens up other trains of thought and realizations about the interconnectedness of joy and suffering and the futility of trying to chase after the one or avoid the other. They are really like two links of a chain. To chase after or avoid those links is only to deform and distort the linkage, never to separate the links. Love and death are like this. We want one and shun the other. With upekkha we hold them together and move into a new way of looking at both.

Of course it is difficult to maintain this kind of awareness. All too easily our mind becomes tainted with aversion and equanimity slips over into cold indifference. Here there is still the perspective of impermanence, but the human empathy is lost. The way to work with this enemy is again by persisting with the practice itself but also by very deliberately bringing in metta.

One last word about the Brahma Viharas which so far I have omitted. They bring beauty into one’s life. It’s a beauty which is permeated more and more with awareness and acknowledgement of impermanence. The harmony which comes of holding beauty and impermanence together is one measure of the great transforming power of these four great catalysts of being.

Add comment