Our Scottish grouse moors are famous world over. They’ve taken centre stage in our novels. Remember Richard Hannay scrambling over the heather in Thirty Nine Steps? They’ve attracted the rich, famous and influential to sit in a cold dugout and try their skill, or luck, with a shotgun as the birds are beaten towards them over the moor. In all they make up 17% of our land area.

It doesn’t look a very attractive or hospitable bit of land. Not helped by blackened heather which gets burnt back as a way of managing the grouse estates. That’s managing as in maximising the income from shooting the birds. Admittedly, grouse moors are by definition the higher parts of our landscape and it’s all just heather, peat and bogs up there, eh? And if it brings income and employment to the locals that’s all to the good. That’s the argument that we’ve heard from the grouse estate owners for some time. It gets trotted out whenever anyone wonders if there might be other ways to use and manage the 1.5million hectares given over to grouse shooting. A hectare is the same area as an international rugby pitch so that’s 1.5million Murryafield.

Are grouse moors the best use of that 17% of Scotland?

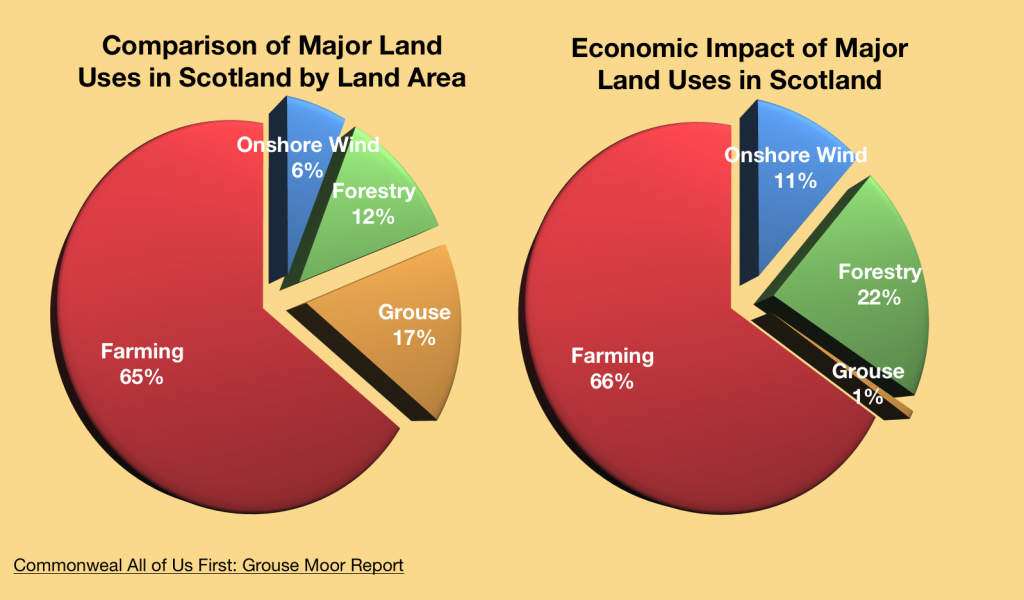

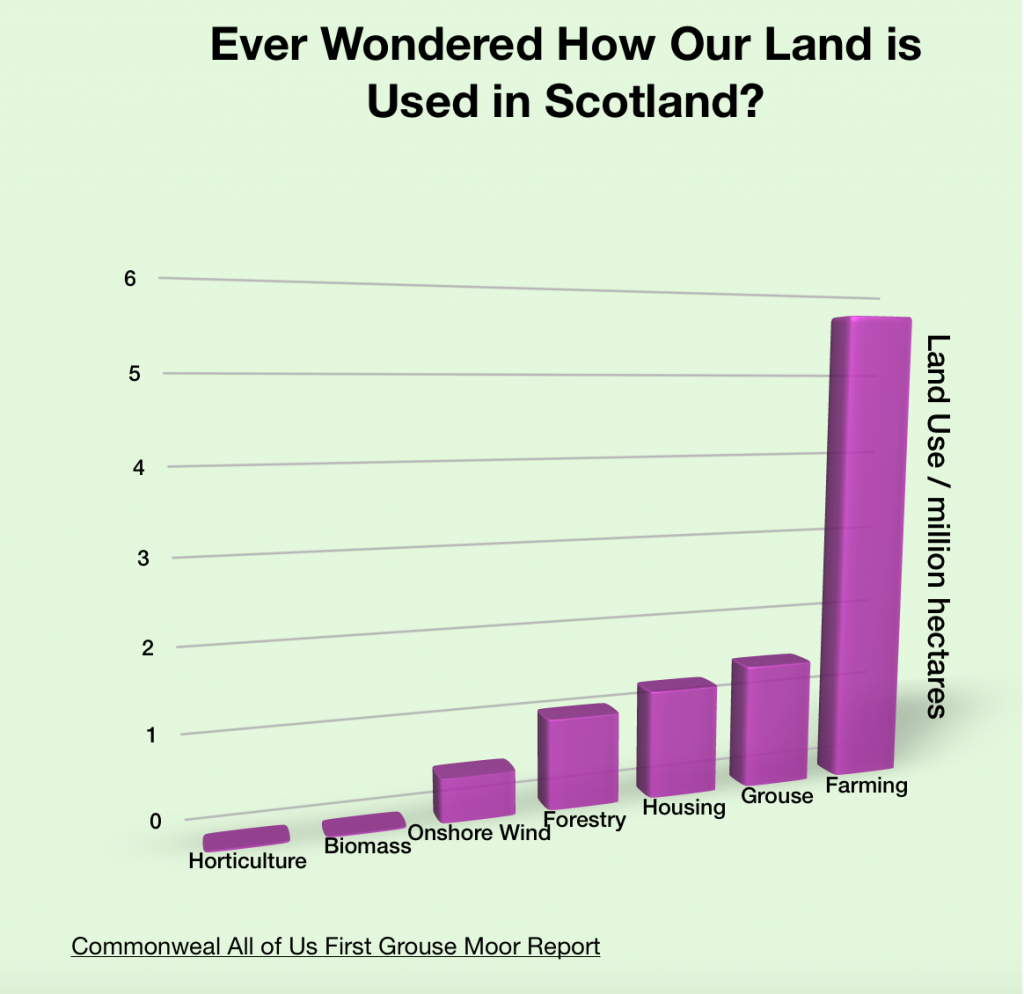

Just for comparison here’s how we currently use Scotland’s land. As you’ll see more land gets used for grouse shooting than the area which houses our whole population.

But that’s OK isn’t it. We wouldn’t want to have our houses perched up there in the rain and wind anyway. And, you know, if it bring income and jobs…. blah, blah.

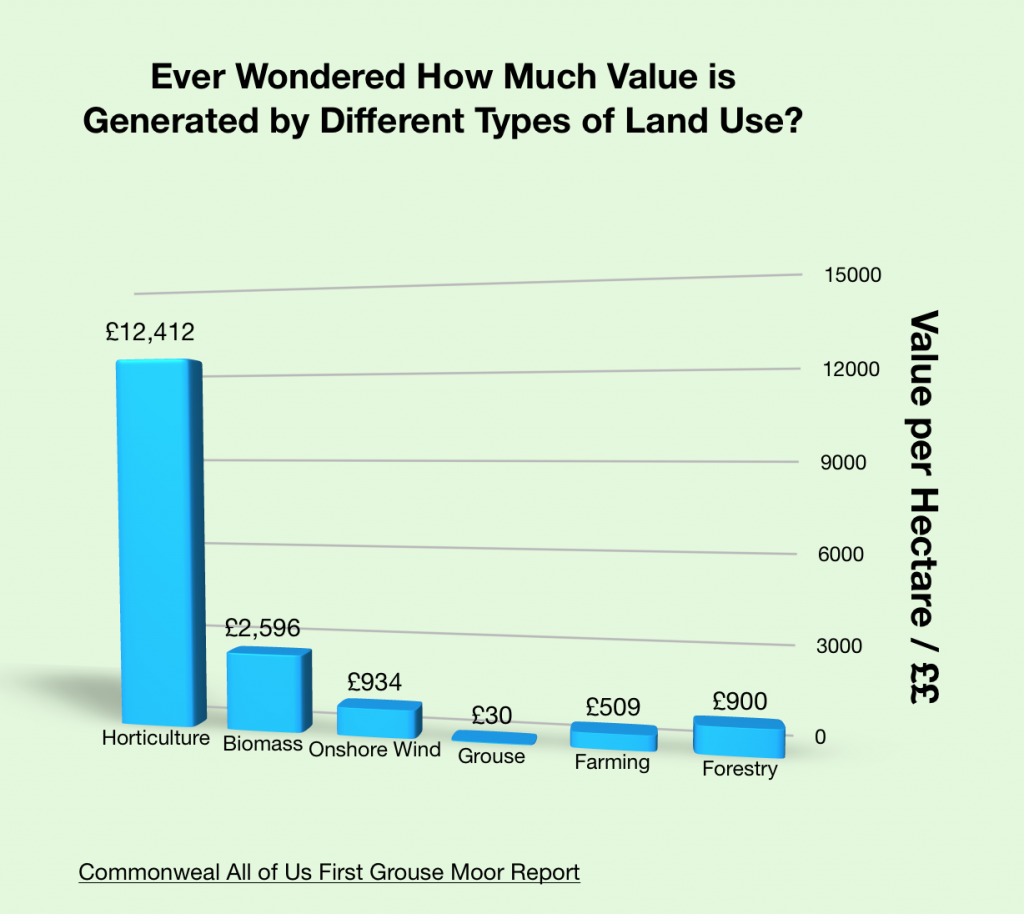

Aye well here’s income it produces.

It really doesn’t look like grouse moors are economically very productive. At this point, we have to stop giving the “it’s the only thing they’re good for” argument any credence. Thirty quid a year income from a piece of land the size of Murryafield? Forestry, wind turbines, biomass plantings all use roughly the same type of land as grouse moors. And obviously they manage to create a lot more income from it. Horticulture is a bit of a special case as it uses very little land but does it very intensively and under cover from the weather.

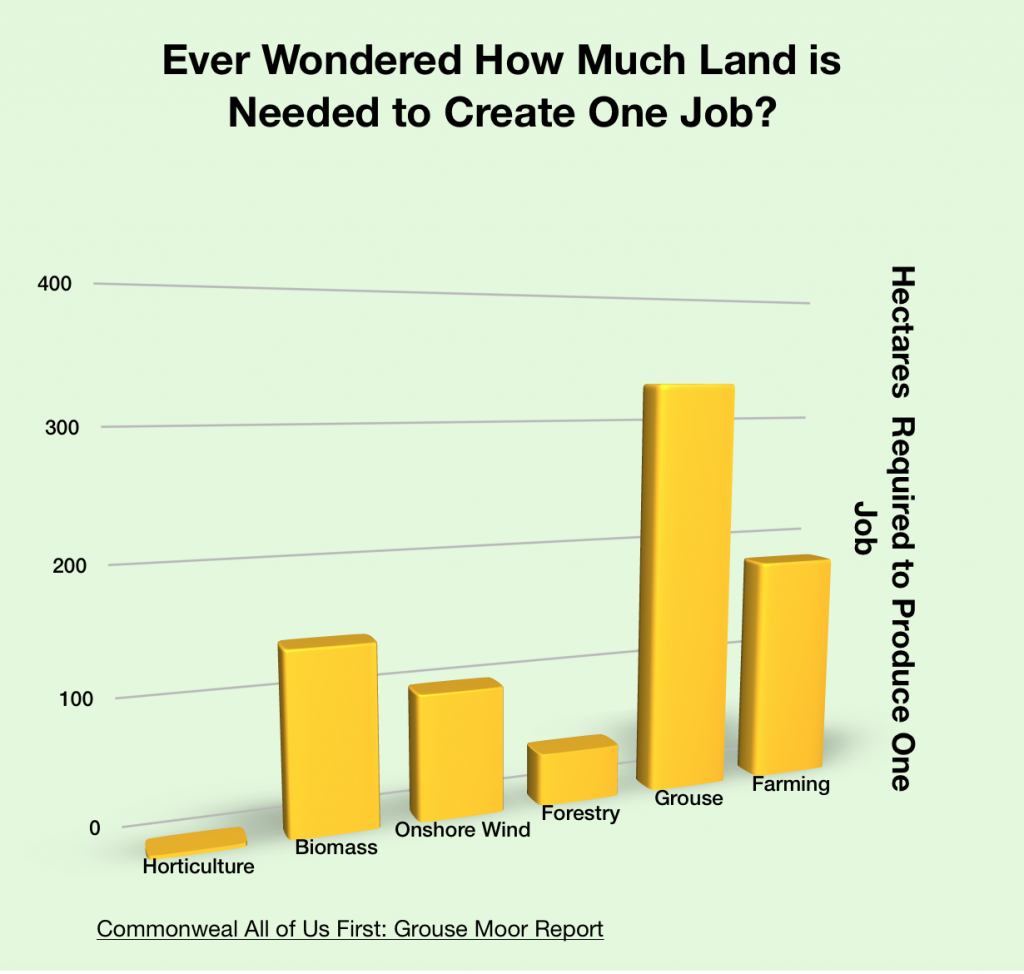

Aye, but still there’s the jobs to take into account too. Right, here’s the info about the jobs.

So basically, we are letting one sixth of our land be used in a way that produces minimal income and minimal jobs compared to other viable options for that land? That doesn’t seem a very good arrangement to me. It’s not as if we have a lot of spare land and surely it’s only sensible to use what we have in the most economically sound way? Not to mention the most environmentally sound way. More of that in Part 2. To sum it up…